Not for you

THIS IS not for you, or so goes the dedication line for Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves. It's a fantastic line that creeps me out a little. It both acknowledges the reader, but also establishes a sense of hostility with them. You're here, but you really shouldn't be. A sort of surreal unnerving quality that I find paradoxically engaging. It's also a feeling I get when I think about the endless list of silent films we've managed to lose over the years. Some were major cinematic events, others minor B-movies, but all existed, and all are gone now. These films are not for you.

I try endlessly to engage in a variety of habits in order to improve my life. Most are simple. Get up earlier for work. Make my bed every morning. Eat better. This one is a little stranger. As I am sure countless comedians have pointed out; there used to be a point in our very recent past when you could be having a conversation with a friend and reach a disagreement, usually about which of two actors starred in a particular film from about 15 years ago. Was it Ben Affleck, or was it Matt Damon? You'd discuss the two actor's careers at the time, each recalling facts, and arguing your position. Nowadays that information is available at our fingertips. With a handful of taps, instant gratification is achieved. A quick look on IMDB. The mystery is solved. Conversation ended. Efficient? Yes. Fun? No.

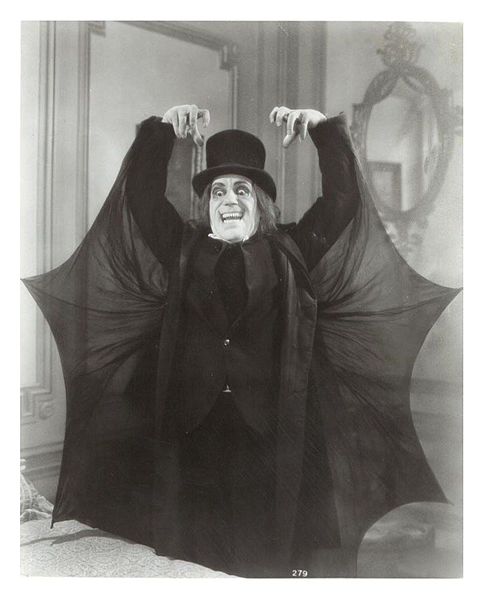

London after Midnight, one of the world's most sought-after lost films.

Mystery solved. Conversation ended. Efficient? Yes. Fun? No.

This is why I think lost film is so interesting - in a world where the sum total of all human knowledge is immediately at hand, this is a small sliver of something which you can't know. Lost films are just that; lost. The Library of Congress estimates about 75% of all silent films are lost forever. We can snatch tantalizing glimpses of them - perhaps a lobby card or two. Maybe a poster. If we're really lucky, maybe we'll have a collection of stills. But the movie is gone. It could be out there somewhere. Sometimes films long thought lost do crop up again. But we don't know where. Many people are involved in the creation of a film. Perhaps quite a bit fewer than the endless armies of computer animators working on a souless modern blockbuster, but certainly enough. Many of these films were their creator's pride and joy. Now they're gone.

The first time you see the photograph series Christina in Red, your jaw drops. This is a series of color photographs taken by electrical engineer Mervyn O'Gorman of his daughter in 1913. The clarity of the photographs and the lucidity of the colors combine with O'Gorman's obvious skill with the Autochrome process to result in a disarmingly modern looking girl. Especially modern considering these were photographs taken more than 100 years ago.

Christina looks surprisingly modern given her photograph was taken more than 100 years ago.

Photographs like Christina's remind us that those who came before us were human just like us. They felt love, embarrassment, fear, and joy just as deeply as us. It seems like an obvious statement, almost foolish as I write it, but I am convinced that while it is something we know, it is not something we usually feel. I look at Christina and wonder, what was her daily life like? What was she thinking? Perhaps that she should really try to make her bed every morning, or perhaps she's trying to recall whether that film starred Lillian Gish or Gloria Swanson?

Legendary filmmaker George Melies, hundreds of his films are now lost.

Something happens to the past when there are no photographs of it. It feels as though it becomes almost cartoonish. I think it's something to do with the quality of the signal we recieve - events from the distant past are boiled down to their most important parts. Great events. Great people. Photographs capture the little details. The crow's feet arround the eyes. The lipstick stained coffee mug on the kitchen table. The cupboard door left slightly ajar. Tiny little untold stories which endlessly enrich the world the subjects inhabit. Lost films are compelling for exactly the same reason. There's usually enough information for you to get the general gist of the movie, but there still remains a million little unanswered questions. It forces you to use your imagination, to really play with the answers, because they sure as hell aren't on IMDB.

The vast majority of films were lost for a fairly explosive reason. Film was often printed on a very flammable nitrate stock. It meant that A) storing film safely was very expensive, and B) it wasn't stored safely. Often studios would abandon or order destroyed the film reels delivered to theaters at the end of their run. It was key point in Bill Morrison's Dawson City: Frozen Time (a masterpiece which I can say without a shadow of hyperbole is one of my favourite films of all time). The films not deliberately destroyed were accidentally destroyed in a series of archive vault fires. Like a modern day library of Alexander, decades of film, lost in a puff of smoke.

Like a modern day library of Alexander, decades of film, lost in a puff of smoke.

Occasionally, copies of these films do resurface; a 1912 version of Richard III was thought lost for decades until a copy was discovered in 1996. Fritz Lang's Metropolis is a particularly strong example of a rediscovered Lost film. But, it's safe to say most of those films lost aren't coming back. It's difficult to accept in a world where the sum total of all human knowledge is at our fingertips, at all times. Almost any movie or TV show can be streamed directly in to the device resting in your pocket, or in the palm of your hand (for a nominal fee). But these films are different. These films are not for us. These films are for Christina.